No, the Zamboni didn’t break down.

No, the Zamboni didn’t break down.

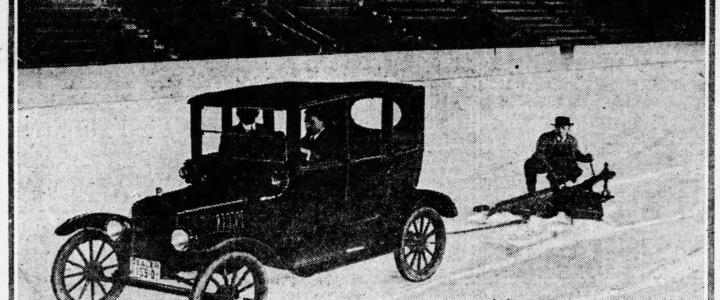

This image from The Oregon Daily Journal on January 13, 1918, shows a crew resurfacing the ice at the NW Marshall Street Rink. It highlights an early improvement over previous methods, which relied entirely on manual labor. Before the Zamboni was invented, ice resurfacing at natural and mechanical rinks involved pulling a scraper behind a tractor—or, in Portland’s case, behind a Ford sedan.

The Ice Hippodrome in Portland faced significant challenges in preparing smooth ice for hockey games. Before the use of motorized vehicles, workers relied on hand scrapers and brooms to remove ice shavings. They then poured water onto the surface, squeegeed off the dirty layer, and finished with a final application of clean water.

The repurposed Ford sedan shown in the photograph was purchased from C.W. Pilchard of the Portland Garage. This innovative setup gained attention after a test drive made local headlines, reporting on the Ford pulling what appears to be a baseball infield dirt scraper. The NW Marshall Street Rink measured 321 feet by 85 feet, making it significantly larger than today’s professional hockey rinks (200 feet by 85 feet) and Olympic figure skating rinks (200 feet by 98 feet). Today, resurfacing a rink takes less than 15 minutes, but before 1950, the process could take up to an hour, resulting in a very long intermission during hockey games.

Creating a smooth ice surface was a labor – intensive process. Workers would first scoop away ice shavings, spray the surface with water, and then use squeegees to remove the dirty water. Ideally, the final step involved applying hot water, which would freeze and create a smoother finish.

The Portland Rosebuds were the first professional U.S. ice hockey team on the West Coast and were nicknamed “Uncle Sams.” They played in the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) and are notable for being the first American team to compete in the Stanley Cup Finals. Although they lost the 1916 finals, their name was still engraved on the Stanley Cup. The Rosebuds played at the Portland Hippodrome from 1914 to 1918 (see Fun Fact #38 about the arena).

America led North America in the construction of artificial ice rinks.

Canadian teams didn’t have artificial ice rinks until 1912, and by 1920, there were only four such rinks in total. During the final year of professional hockey at the Hippodrome, the rink’s owners experimented with a motorized ice resurfacer, a precursor to the Zamboni (which was patented in 1953). Beneath the Hippodrome’s concrete floor were 20 miles of pipes carrying 12-degree brine to keep the ice frozen. The refrigeration system was powered by compressed liquid ammonia, which expanded in pipes running through a massive brine tank. The cold brine was then pumped through the rink’s pipes, freezing the layer of water above the flooring.

After their 1916 Stanley Cup appearance, the Rosebuds played two more seasons before relocating to Victoria, B.C. Today, the “Rosebuds” name is used by the Portland Winterhawks hockey team’s dance troupe, which practices at Lloyd Center Ice on Wednesday nights.