The rose wrapping that popped up on the building at 315 NW 23rd honors Rose’s Restaurant, a business started at this location by Rose Garbow Naftalin in 1956. Rose’s was a popular place for significant events and good memories. Wedding proposals like that of Sen. Mark Hatfield were not uncommon.

Rose listed the business for sale in 1967, selling to Max Birnbach and Ivan Runge in May 1968. The men had started out at the Benson Hotel, where Max had been the catering manager & Ivan had been the executive chef. They were still listed as owning the restaurant in 1982. Max Birnbach was true to Rose’s legacy and was smart to keep the quality the same (some say even better). Reporter Joan Johnson interviewed Max Birnbach for The Neighbor in January 1985 “Birnbach, who was born in Vienna of Jewish parents, was in his early 20s when he was put in a concentration camp…He managed to escape and fled with his brother to Switzerland where they were interned in a labor camp.” His parents died in Auschwitz. Max was assigned to the kitchens in the labor camp. He attended a hotel restaurant school in Zurich after the war.

The original location on NW 23rd shuttered in 1993. The building was remodeled in 1994 for Restoration Hardware. Rose’s Restaurant was revived in 2001 by Dick Werth and Jeff Jetton and opened its doors on NW 23rd & Kearny (currently the location of Bamboo Sushi). According to Business Journal’s Wendy Culverwell (12/4/2005) “Though [Werth] dreamed of reviving Rose’s at its original location, the vision foundered.”

Rose learned to cook from classes by mail. Inquiring minds want to know—did her teacher get to taste her cooking?

Rose Garbow Naftalin was less than 5 feet tall and 100 pounds soaking wet. She was born in today’s Ukraine on March 18, 1898. She moved to Chicago with her family at age five. At 19 she married Mandel Naftalin, an accountant who loved good food. She had no training in the kitchen and she wanted to please her husband. She was tenacious; she took correspondence courses in cooking and read cookbooks and asked friends for culinary advice. During the Great Depression Mandel lost his job and he was confident that her amazing cooking could support the family. They bought a deli together in Toledo, Ohio. She cooked food in their home and they took turns running the shop so that one of them could always be home with their two children. After he died in 1939, she ran the deli alone.

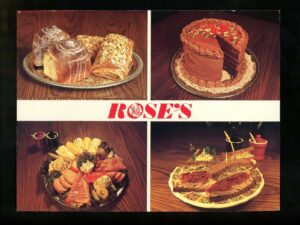

Rose moved to Portland in 1955 to be near her family and opened Rose’s Restaurant on NW 23rd the next year. Her old-school Viennese pastries and New York-style deli kosher deli mainstays developed a following. She was known not only for her amazing quality and generous portions but for a generosity of spirit—baking 7-layer cakes for community members as gifts on their birthdays. She retired in 1967.

Customers remember fondly the authentic Reubens, matzoh ball soup, and famous giant cinnamon rolls. What customers may have forgotten was that the lounge, not the restaurant, covered the expenses. Rose told the Oregon Journal (10/25/78) that the cocktails at the lounge “pulled me out of the red many a month”—that was the best end of the business.

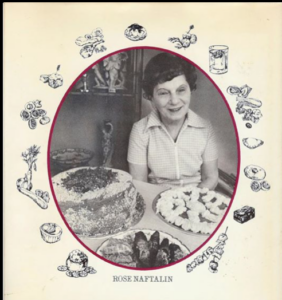

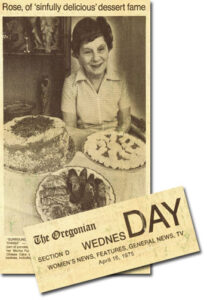

She did not slow down in retirement. She wrote two cookbooks that promoted what was now a chain of restaurants. She wrote her first cookbook, Grandma Rose’s Book of Sinfully Delicious Cakes, Cookies, Pies, Cheese Cakes, Cake Rolls & Pastries, in 1975. Published by Random House, it sold more than 150,000 copies in 12 printings. She followed that in 1978 with Grandma Rose’s Book of Sinfully Delicious Snacks, Nibbles, Noshes & Other Delights. Rose’s recipes were indeed sinfully delicious.

The cookbooks were a way to heal the relationship with her daughter-in-law after the death of Rose’s grandson. Their unique home-spun presentation of recipes and photographs contributed to their success. The 1978 cookbook became the third most popular cookbook that year, behind those by Julia Child and James Beard. The woman who learned to cook by mail, whose restaurant at 315 N.W. 23rd Ave., became one of the earliest hangouts for fine food in Northwest Portland, was now one of the nation’s leading cookbook authors. She filled her retirement years traveling the country in signing books and giving cooking demonstrations. Beloved for her community spirit, she died at age 100 on April 16, 1998.

Her advice to readers: keep split vanilla beans in the sugar and always use real butter because quality ingredients are the key to baking.