Answer the first park in St. Johns was Cedar Park. You still will get full points if you answered Pier Park which is the oldest remaining park in St. Johns and the first public park in St. Johns. After the timeline there is additional information on Cedar Park.

St. Johns Parks Timeline

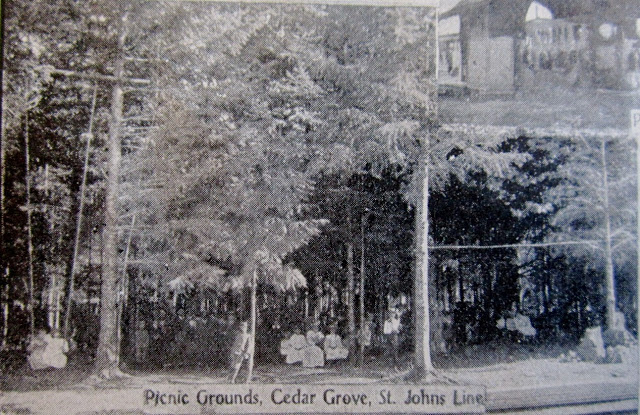

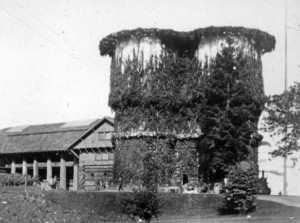

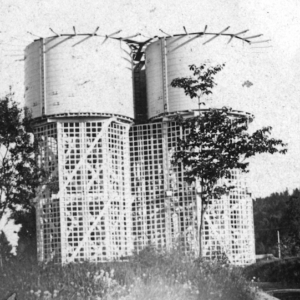

c.1899 Cedar Park 3 acres – 10 acres Location: North Fessenden Pier. Named for the plentiful cedar trees in the park offered for sale $10,000 in 1907 trees cleared in 1909.

1920 Pier Park 87 acres 10325 N. Lombard Street. Named for Stanhope S. Pier in 1921, who served as a Portland city commissioner in the late 1920s and as acting mayor in 1931.

1932 Chimney Park 16.76 acres Location: 9360 N Columbia Blvd. Named the city incinerator chimney that was once at the site.

1941 St. Johns Par 5.77 acres Location: 8427 N. Central St. Named for pioneer James John who settled in the area in 1846.

1968 Cathedral Park dedicated opening in 1980 23.31 acres Location: N Edison Street and Pittsburg Ave. Named for the gothic arches under the St. Johns bridge.

1971 George Park 2.03 acres Location: N. Burr Ave. & Fessenden St. Named for US Congressman Melvin Clark George.

2015 “White Oaks” Location: N. Crawford St. & N. Polk 2.92 acres Former property of Simon Benson’s child, unnamed parked but there are two heritage white oak trees on the property.

More History of Cedar Park

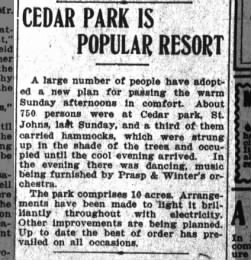

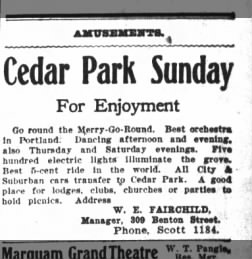

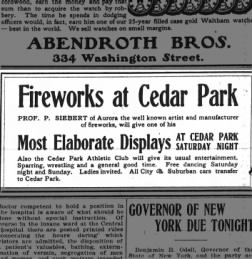

The first park in St. Johns was Cedar Park; a private park owned by City and Suburban Railway Co. Lines Steam streetcars operated by City and Suburban Railway Co. Lines reached St. Johns in 1889. By 1900 the company’s trains arrived at St. Johns every 20 minutes. Cedar Park was owned by City and Suburban Railway Co. and leased out to various managers over a few years. There was a station a Cedar Park/Cedar Grove servicing the popular picnic amusement park with 500 electrified lights, a merry-go-round, little miniature railway (moved to Mt. Tabor). The first electrified trains reached the park in 1903.

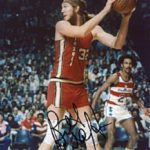

Before moving to Portland’s Nob Hill, the San Diego native was college player of the year playing at U.C.L.A., 1970 -1974 where he led the Bruins to 88 consecutive wins and two national championships. In 1977 Trailblazer Bill Walton was the Grand Marshall of the event “Splash,” a neighborhood fair and parade. The parade went from Couch Park to Wallace Park. His basketball career ended in 1986 after a foot operation. His connection with the Patty Hearst kidnappers, radical activists Jack and Micki Scott, is still being explored.

Before moving to Portland’s Nob Hill, the San Diego native was college player of the year playing at U.C.L.A., 1970 -1974 where he led the Bruins to 88 consecutive wins and two national championships. In 1977 Trailblazer Bill Walton was the Grand Marshall of the event “Splash,” a neighborhood fair and parade. The parade went from Couch Park to Wallace Park. His basketball career ended in 1986 after a foot operation. His connection with the Patty Hearst kidnappers, radical activists Jack and Micki Scott, is still being explored.